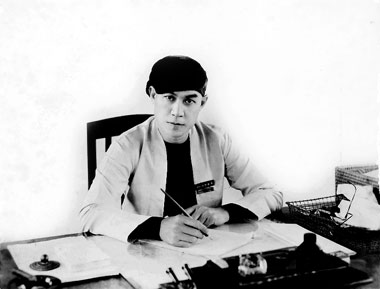

Dr. Ba Maw, the Man

As Told by Mala Maw

Written by Nell K. Murry

Scholar; charismatic speaker; author; altruist and champion of the poor; husband and father, this was Dr. Ba Maw, the man. Above all, he was a nationalist; a revolutionary; a leader; a politician and a brilliant statesman. He led the fight to unshackle his country, Burma, from the chains of colonialism, steered her towards independence, and became her first prime minister. But who was he? Where had he come from, and what were his roots, this man, this Dr. Ba Maw?

He and his older brother, Dr. Ba Han (1890-1969), were born in Maubin, Burma (now Myanmar) to Daw Thein Tin and her husband U Shwe Kye, an official of the courts of Kings Mindon and Thibaw.

In his youth, their father U Shwe Kye, studied English at Dr. Marks’s American Missionary High School in Moulmein; he also learned French, hence he was well-acquainted with western culture. Upon his graduation, he was appointed tutor to King Mindon, and moved to the royal capital, Mandalay. There, his talents were recognized, and not long after, he was tasked with accompanying then Prime Minister Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung to London and Paris to sign a friendship treaty with Britain. As E. M. Law-Yone wrote, “It was the first time a Burmese plenipotentiary had ventured into the heartlands of the infidel. U Shwe Kye alone could communicate directly with western leaders, and this earned him ambassadorial rank….”

Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung, in his London Diary (written in Burmese in Rangoon 1908), describes this goodwill visit in detail (q284 B.E., 1872 A.D), and categorically states that he was accompanied by U Kye (Ibid Vol. 1 pp 383, 416, 417, 433, 443, 447). Known as the Kinwun Mingyi Diary, this account of the diplomatic mission is one of the most important documents of early modern Burmese history. It is believed to have been penned by none than U Shwe Kye, who was then considered an exceedingly rare individual in Burma, for in the latter half of the 19th century, as men who had traveled abroad, and were familiar with western views were practically non-existent.

While Lower Burma had been colonized after the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1852, Upper Burma remained a sovereign kingdom. The Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 sealed her fate; the British took Mandalay and exiled her last ruler, King Thibaw, to India. When the fervent nationalist and staunch royalist, U Shwe Kye, learned of these developments, he went underground. He returned to his hometown, Amherst, the present-day Kyaikkami, some 300 kilometers southeast of Rangoon. There, he set about organizing an anti-British movement, and to gain heavenly grace for his cause, he donated a pagoda. It still bears the inscription “By virtuous merit of U Shwe Kye.” Sadly, from the day of his departure, his two little sons, Ba Han and Ba Maw, never saw their father again.

Life now, was not easy for the family. The boys’ mother, Daw Thein Tin, was without means of support. Nonetheless, she started a small business with a pony cart, and though in later years the business grew into a fleet of gharries or hackney carriages, she was, at that time, in some financial straits. Nevertheless, forgoing luxury and sacrificing her own needs, Daw Thein Tin struggled tenaciously to provide for her sons; she worked tirelessly to find a way to educate them.

About that time, the family lived in a town, where only an insular education was available, one that was geared towards Burma herself. Daw Thein Tin knew this was no longer sufficient. The outer world had encroached, and if her sons were to reach their potential and achieve, they had to have a modern-day education, one that was equal to the education being given to the children of the well-educated foreign invaders; in short, a western education.

After some research, Daw Thein Tin determined that she would send her sons to St. Paul’s Boys School, an elite boarding school in Rangoon. She realized that she could not afford such an expensive school, but having done her research, she now persevered in making the arrangements to get them in. This was no mean task as she did not have the convenience of the automobile, the telephone or the Internet, and letters took longer than a week to arrive at their destination. Nonetheless, she was resolute, and finally her efforts brought success; her sons were accepted by the school, each on a compassionate scholarship. They did not have the privileges of parlor boarders, but the education provided to them was the same.

To these two proud boys, it was a humbling experience. Nevertheless, this humiliation, plus the pain of separation from their beloved mother, had an unusual advantage: It stiffened their resolve into a steely determination to study diligently, and follow in their father’s footsteps.

Ba Han and Ba Maw easily excelled in school, and later, in graduate studies. In due course, they earned their doctorates, and went on to successful lives. Much to their regret, however, they were never able to give their mother a more comfortable life, one that she so richly deserved. Instead, she had to struggle for it herself.

The influence of his childhood poverty is seen in Dr. Ba Maw’s conviction that good health and education are of prime importance in a successful life. Caring deeply that his children understood this concept, he constantly reminded them to focus on these twin aspects as their first priority.

Concerned also that his children open their hearts altruistically, he advised them never to forget the underprivileged, or their own debts of gratitude. He often told of how grateful he was to his eldest cousin, who had enabled him with financial assistance to complete his bar exams abroad. This act of kindness, he said, had led to the eventual launching of his political career and premiership. “You are blessed,” he would tell his children, “and the best way to show your thankfulness, is to share your blessings, whenever possible, not only with your kin, but also with the less fortunate.”

It is reiterated here that Dr. Ba Maw and Dr. Ba Han were not sons of privilege; neither was success handed to them as a gift. Instead, they suffered many deprivations in their early years, yet through their innate abilities and single-minded diligence, they faced their challenges and achieved greatness, Ba Han in law, and Ba Maw in politics.

Dr. Ba Maw was a dedicated nationalist, a gifted politician and a visionary far ahead of his time.

By far the most learned of the nationalist agitators against the British imperial presence in Burma, Ba Maw received his high school diploma from Rangoon College, and as he was graduated with such brilliance, relatives and friends made it possible for him to attend Calcutta University, India. There, he obtained his Master of Arts degree. Then, following in his brother’s footsteps, Ba Maw was admitted at Cambridge University, England, and entered Gray’s Inn to study law. In 1924 he qualified as a barrister-at-law. Later, he did research at Bordeaux University, France, wrote his dissertation, “Aspects of Buddhism in Burma,” in French, and earned his doctorate in Philosophy, suma cum laude.

Upon his return to Burma in 1924, Dr. Ba Maw entered the practice of law. His elder brother, Dr. Ba Han (1890-1969), who was a lexicographer and a legal scholar as well, did the same.

While practicing law, Dr. Ba Maw became interested in colonial-era Burmese politics. His interest rose from his defense of the nationalist Saya San, who was charged with seditious treason for having started in 1931, a tax revolt that had captured the popular imagination. Even though he knew the case was a lost cause---no other lawyer would touch it---Dr. Ba Maw stepped forward and courageously defended Saya San. As foreseen, the case was lost. However, it made a lasting impression on Ba Maw and the public. He could not fail to see how clearly it emphasized his earlier observations of the plight of the down-trodden, especially the peasants. They toiled daily, yet they could not struggle out of the morass of their debt-ridden lives. He vowed to break this vicious cycle of poverty, illiteracy, poor health, and shortened life-spans that blighted the masses, his countrymen.

Dr. Ba Maw felt the impact of western imperialism early in his childhood. Though he was but five years old during his first encounter, the racial discrimination of the ruling class affected him traumatically. The following incident remained engraved in his memory forever: A fair, English boy riding a shining, bright-red tricycle; his deep longing for one like it; his drawing near for a closer look; the ugly grimace on the nanny’s face; her rude shouts; and the final humiliation, being driven away as so much scum. He was not even good enough for a quick look!

This experience scarred him deeply. And because in his child’s psyche “happiness is a shiny tricycle,” he understood the yearning of children for toys; and their great disappointment when finding them beyond reach, simply because of the yawning divide between the haves and have-nots. He felt for these children, and vowed to fulfill the wish of every poor child whenever he could.

Dr. Ba Maw was a sensitive, compassionate man. He was profoundly touched, when he was told the story of his father’s deep distress as he witnessed the beloved Royal Family in the royal barge, slowly floating past Maubin on their way into exile, how they had waved sadly at the huge mass of grieving townspeople gathered on the banks of the river to pay their respects. Dr. Ba Maw vowed, that the day would come, when Burma would regain her sovereignty and be at peace with the world.

In 1934, during his tenure as Minister of Education (and later as Minister of Health, and then Premier), he conceived of, and brought to fruition, a plan for the awarding of state scholarships to post-graduate students; he initiated the formation of The Religious Ministry. He abolished the five-rupees tax that the British levied on every citizen, a tax so onerous, that farmers and the impoverished were crushed beneath its yoke; and he introduced the State Lottery paying a monthly cash prize of Rs.100,000- just so a few lucky winners could experience the joy of riches.

Dr. Ba Maw left his family a legacy of memories, most of them replete with morals and instruction. The last memory he spoke of was about a small Burmese village that he discovered on the Burma-Siam border at the end of World War II. Here was a veritable Shangri-La! For the older generation lived life guided by the simple philosophy of need, not want: A small, clean house with a small, neat garden; a small, nearby pagoda; a small school; a clinic; nourishing food in sufficiency; decent clothing; quietude of heart to see only the good in people, even in enemies; and finally, a life of good health, peace and harmony to the end of their days. This to them spelled “Happiness,” and which they had in abundance.

Dr. Ba Maw did not condone cruelty, injustice, unfairness, irresponsibility, bribery, or any kind of corruption. He always said that if one wanted rights, one must show responsibility. He was a man who wanted to do so much for his country, but with all that there was to do, time would never be enough. He hoped his children would continue his altruism, and instilled in them those values that he held most dear. Again and again, impressing on them the principle of a good education as the foundation-stone for a better life, he encouraged them to follow the tenets of Buddha: Metta, Karuna, and Mudita: loving kindness, compassion and sympathetic joy to be shown to, and shared, not only with relatives, but also with poor, but bright and promising children.

Because Dr. Ba Maw was a towering figure in the Burmese political arena, and because of his brilliance and compassion, he was regarded with awe. Even his adversaries respected, and perhaps even admired, his political savvy and accomplishments. E. M. Law-Yone wrote, “Upon Dr. Ba Maw’s death, the nation mourned him. Despite the ban on public gatherings, one thousand of the elite of Burma came to pay their respects….”

Today, as conscientiousness and hard work have brought stability and security into the lives of the present, three-generational Maw family, they ardently seek to bring their forebear’s noble aspirations to fruition. Towards this end, they have established a library and a foundation in his name.

October 2012